I have decided to share some of the entries from the book from time to time on this blog.

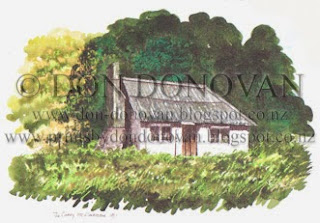

I first saw this cottage in 1965 when with my wife Pat I was on a Sunday afternoon sketching expedition. Its symmetry and classical proportions seemed to characterize it as a typical house fit for a typically successful but modest Wairarapa farmer.

I sat in the car, totally absorbed, scratching away on my sketchpad with an old fountain pen until, almost before the Indian ink was dry, she whipped the finished drawing away and with the cheek of an encyclopaedia salesman marched up the garden path, knocked on the front door and sold it to Brian McEwan, the then owner!

We never saw him again but I never forgot the cottage and was pleased to draw it again and include it in this collection over thirty years later.

It’s not easy to get information about the cottage because, although transfers of land are carefully recorded, the fates of buildings are not. A crown grant of 166 acres was made to William Parfitt Nix and Josias Tocker, Hutt Valley farmers, on 15 March 1854. Nix died that year, leaving his son, Lewis, and wife, Mary Ann, as executors. She subsequently married Christopher Potts* to whom the title transferred in 1870. The land that the cottage stands upon was part of that grant.

The holding was broken down over time and bits were sold off, but in 1884 Potts was issued with a certificate of title to fifteen acres which included the cottage. It was registered in his wife’s name and so, when Mary Ann died in 1900 it passed to her son, William Nix. It stayed in that family until 1954. It was then was bought by John Donald who subdivided it ten years later and sold one-and-a-half acres with residence to Brian Peter Douglas Fitzgerald McEwan. Which is a long winded way of establishing that when I did my first sketch of ‘The Cottage’, McEwan had only recently bought it.

Nick and Lesley Shalders, the present owners, believe it may date to as early as 1860.

The barn, constructed of pit-sawn timber and handmade nails, boasts a long-drop and was probably a milking shed. It may be as old as the cottage.

*Interesting: When researching my book ‘The Good Old Kiwi Pub’ I discovered that the nearby ‘Tin Hut’ hotel was once owned by C Potts - the same man - a land owner of local note thus meriting the title ‘gentleman’.

© DON DONOVAN

donovan@ihug.co.nz

.