I wrote and illustrated ‘New Zealand House and Cottage’. It was published in 1997. It’s a snapshot of some historic New Zealand homes - both grand and modest - as they were preserved at the end of the 20th century.

I have decided to share some of the entries from the book from time to time on this blog.

This is a personal collection of houses and cottages that I have gathered over recent years when travelling around the country looking for various ‘paintable’ buildings, subjects ranging from country pubs and general stores through courthouses and churches to grand mansions and simple cabins.

There’s no ’scheme’ to the book. It is not organized in any way other than to present visual variety, page by page. What all of the subjects have in common, I daresay, is that in their lifetimes they have been cherished by at least some of their occupants. It is that emotional attachment which makes a house a home and many of the privately owned properties on the following pages are cherished to this day; proof of that lies in the enthusiasm with which their owners have supplied me with information.

Other properties of such historical significance that they are now protected by institutions such as the New Zealand Historic Places Trust are no less cared for even though their rooms may be little other than museums; it is only regrettable that for want of resources not all worthy relics may be preserved and so the country is dotted with once-loved derelicts such as the house near Brightwater that is the tailpiece of this book.

Marketing psychologists say that the human race’s only needs are a blanket, a piece of meat and a cave. These are essential to survival: all else is luxury to a greater or lesser degree. When we walked out of our caves and started to fashion our shelters we added a cultural dimension - architecture - and with it came love and pride of home.

I’m certain that when James Reddy Clendon built his simple house on the cliffs of the southern Hokianga Harbour at Rawene he lavished as much love upon it as did the owners of grander mansions like Thomas Marsden’s Isel House near Nelson or Allan Kerr Taylor’s Alberton. Shelter was fundamental but beyond that, shape, space, proportion, utility, decoration, ‘atmosphere’ and layout of the grounds and gardens presented opportunities for creative planning of domestic comforts to mind and body. I’m thankful for that for I doubt that I could raise much excitement over making watercolour illustrations of caves.

With one or two exceptions the subjects are discrete houses or cottages, but I’ve also found some multiple dwellings of interest such as Dunedin’s classical terrace of town houses in Stuart Street, and a charming, mirror-image brace of workmen’s cottages in George Street.

Mokai

There’s also the fascinating row of timber mill houses, built around 1903, bordering the remains of a village green at Mokai, north of Taupo: they’re virtually all that’s left of a town which, in its heyday, had a billiards saloon, race track, dance hall and sly grog shop - sly because of prohibition. Smoke still rises from the chimneys of the houses but the Mokai Mill closed over forty years ago.

The same type of dwelling has always been built by large corporations or government agencies whose industries and work forces have been large enough to warrant it; although not illustrated in this book, one thinks of timber-town houses in Tokoroa; workers’ cottages at the cement town of Portland or around various electricity power stations, and that fine range of New Zealand Railways’ designs erected all over the country, many of which have disappeared while those remaining are fast becoming collectors’ items to be restored with affection.

The big mansions are impressive (and suggest that despite current fashionable ‘have-and-have-nots’ debates the spectrum of social status was far greater in the early days of European settlement than now) but I’m even more awed by the simple shelters of the pioneers.

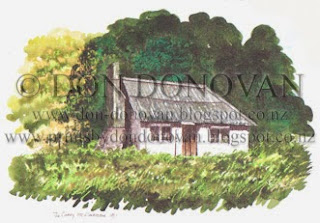

A good example is the ‘Cuddy’ built in the 1850s below Mt. Gladstone, a peak in the Inland Kaikouras overlooking the remote Awatere Valley. A long, winding, dusty drive from the Marlborough coast to get there today, the difficulty of access and the lengthy isolations of the mid-nineteenth century are almost unimaginable. Despite that, it is not hard to picture the welcoming cosiness of the Cuddy’s tiny living room with a crackling fire inside and forty-five centimetres of cob wall keeping its occupants safe from the wintry blizzard.

Patersons Accommodation House

A similar haven would have been Paterson’s Cottage, a cob-walled, shingled accommodation house built in 1872 for travellers in the Waitaki/Hakataramea area. It looks forlorn these days isolated in a paddock off the highway, but to a tired, rain-sodden 1890s drover the yellow light spilling from its windows would have promised paradise even though he might have had to share the ripe atmosphere of the loft with several others.

It’s interesting to observe that many of the old cob cottages of the pioneers may be found close by the gracious houses now occupied by their descendants. It rather argues that their forebears were by no means privileged, they earned their success through sweated perseverance. Couched on a peaceful hill and surrounded by periwinkle, the cottage at the romantically named Glens of Tekoa near Culverden is one such, but the best example is another ‘Cuddy’, this one at Waimate in South Canterbury which was built by the Studholmes in 1854 and is still in the family. It’s such an unbelievably picturesque cottage of snowgrass thatch and totara slab surrounded by English country garden flowers and green baize lawn that I was diffident about painting it - it’s almost too pretty.

I make no apology for the accidental emphasis on Akaroa. I could do a whole book on that pleasant little town which, it seems to me, has the highest concentration of picturesque cottages in the land. It’s a town that has been ‘discovered’ in the last twenty years and many of the houses, which had gone past their best, have been rescued and restored by locals and Cantabrians both for permanent dwellings and holiday homes. The town exudes a fierce pride and, it seems, a daily dedication to becoming more and more Gallic, knowing that its French colonial origins make it unique; but so far it has, thankfully, resisted the temptation to exploit tourism to the point where, as has happened in Queenstown, the old enchantment is obliterated.

There are no baches or cribs in this book. They epitomise a unique and irresistibly attractive side to the New Zealand character but they are, in general, a class apart from the serious family dwelling. While, I know, some people live in them full time and some of them are quite elaborate, they are quintessentially holiday homes inextricably linked to long days of seaside sunlight, sand in the cracks between the floor boards, bush flies buzzing behind flimsy net curtains and the heavy aroma of barbecued chops hanging over the bay at twilight. They might be the subject of another book …

And there is nothing modern here: the future will identify the treasures of today but it’s hard to pick what’s going to become a classic. Will tomorrow’s exemplars be gaunt, white, factory-chimneyed fibreglass ‘eccentricities’ or some of the status-symbolic, porte-cochered mini-mansions of Auckland’s North Shore sub-divisons - who can tell? I certainly can’t. Besides, on the houses and cottages I paint there’s a patina that can only come from age. I hope you’ll enjoy sharing it with me.

Don Donovan. Albany 1997

© DON DONOVAN

donovan@ihug.co.nz

.

No comments:

Post a Comment